The Weaverbirds, Y.B. Mangunwijaya, 1981

- Indonesia, #10

- Kindle, $10 on Amazon.com

- Read June 2017

- Rating: 2.5/5

- Recommended for: boring people

In brief, this book is about childhood sweethearts who end up on opposite sides of the Indonesian revolution. Setadewa and Atik are both connected to Javanese royalty, and in childhood their paths cross in the court. Later, Setadewa joins the Dutch colonial army to fight the Japanese during World War II, which puts him, after the war, in opposition to the Indonesian forces fighting for independence. Atik, on the other hand, “become[s] a young woman who burn[s] with the zeal of a just cause. The flame that had been set free by Soekarno‘s freedom movement burned brightly within her.”

It’s an interesting look at the shifts in Indonesian attitudes and culture around the independence movement of the mid-20th century. In the earlier novel Sitti Nurbaya, the hero joins the Dutch colonial army, while the villain leads a small rebellion: clearly at that point, popular sentiment (or at least the popular sentiment that made it past the censors) was with the colonists. In The Weaverbirds, published in 1981, sympathies are clearly with the revolutionaries. However, there are some intimations that, with hindsight, Indonesian independence is not the paradise that the novel’s characters hope it will be. One passage that particularly stood out in my mind is one in which Atik’s parents are complaining about the cruelty of the Japanese, who occupied Java during the war. Atik’s mother says, “Well, if Indonesia gets its freedom, we’ll never be that cruel.” Now, this book was published ten years before Indonesian troops massacred hundreds of Timorese civilians in the Dili Massacre, but Indonesia had already been occupying East Timor for six years, and the inhumane “fence of legs” program began the same year this book was published. This was also the middle of Suharto’s thirty-year presidency; Indonesia’s second president has been called “the most corrupt leader in modern history” by Tranparency International. According to wikipedia (yeah, I do the deep research for these blog posts), by the 1980s “Suharto’s grip on power was maintained by the emasculation of civil society, engineered elections, and use of the military’s coercive powers.” Mangunwijaya thus gives Setadewa the rather prescient realization that “the mistake in the nationalists’ logic [was] thinking that a country and its people were the same thing. They figured that if the country got its freedom it would follow that the people would get theirs.”

So, there are some interesting concepts explored here, and some riffs on the doomed love stories and complicated explorations of revolution that we’ve seen before. But it just isn’t a very good book. There’s a lot of icky-weird discussion of gender and desire (“Atik’s womanhood, I knew, was as vital as the tropical forests that yearn for the dark rain clouds and the masculine thunder that heralds the coming of the monsoon,” to which I made the note, “are you sure you’re going to be able to deliver that monsoon, lover boy?”), including the conflation of romantic and sibling love seen in Sitti Nurbaya and This Earth of Mankind. Possibly the weirdest passage, for me, was when Setadewa and Atik encounter each other unexpectedly while on opposite sides of the revolution. Seta looks into her eyes and is frightened at first, but afterwards he thinks to himself, “No, her shining black eyes were not the ominous ends of two gun barrels, but rather the dark nipples of a mother’s breasts. And I, at that moment, was not in reality a soldier at all, but a child, a baby, crying out for life and a woman’s care.” (my note on this little paragraph: “wut.”)

There’s also the weird scene in which Atik defends her doctoral dissertation and one of her examiners goes off on an existential tangent, asking

What meaning is there to be found in the breathtaking beauty of the creatures that have been present in the forests, the oceans, and the sky long before the coming of humankind? Is it possible that the beauty we see in the animal kingdom, or in the rose, is nothing more than a mindless play of nature, completely coincidental and devoid of meaning?

Now, I dropped out of academia after my masters, so I can’t say for certain that biology thesis defenses don’t ever turn into philosophical discussions along the lines of 2 a.m. freshman dorm debates, but this guy seems to a) have a pretty weak grasp of the concept of evolution, and b) be sorely in need of some brushing up on scientific theories of consciousness. This particular example might seem a small matter to a non-biologist, but the text was full of little instances of things like this, minor discordant details, overblown prose, failures of research or imagination that took me out of the story, which, even without these problems, wasn’t a very compelling narrative.

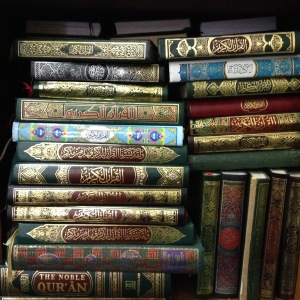

A note about the pictures: The Weaverbirds opens with a prologue, “Prelude to a Shadow Play.” Shadow puppetry, called Wayang kulit, is a very important part of Indonesian culture. It doesn’t really come back into the story of The Weaverbirds, but presumably the prologue, which tells the legend of Larasati, Atik’s namesake, is meant to set up the novel as a sort of folk-epic in the Indonesian tradition. I’m not sure it succeeds, but I thought this would be a good opportunity to use my pictures of Indonesian puppets from the San Francisco Asian Art Museum. These are NOT shadow puppets. They are Wayang golek, rod puppets. But it seems fitting with the general choppiness and sloppiness of this novel that I would use pictures of something not quite the right thing.

“Hey. My eyes are up here”. Best photo caption ever.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I love your marginal (or maybe they’re on a separate sheet of paper–it doesn’t matter) comments. And for what it’s worth, if I remember my history correctly, Suharto came to power after a massacre of supporters of his predecessor, Sukarno.

LikeLike

Oh, that’s a good piece of information. I just looked it up on wikipedia and apparently half a million people were killed, which seems like a pretty crucial piece of information I should have included. I’m currently reading books from the Philippines and writing about Indonesia and I’m getting a little confused about the multitude of power transitions that happened in these two countries in the last century or so.

LikeLike